Books Worth Reading

Here’s a list of books that I think are worth reading. I’ll add books to this list from time to time…

Here’s a list of books that I think are worth reading. I’ll add books to this list from time to time…

The following case study was originally published at the Management Innovation Exchange. Paul won the inaugural Harvard Business Review/McKinsey M-Prize for this publication.

Summary

Morning Star creates a software system that serves as a commercial social network, where colleague commit to their Colleague Letter of Understanding (CLOU) to accomplish specific activities. These CLOU commitments are open and accessible, making roles and responsibilities clear to all, and placing the responsibility for addressing performance issues upon those to whom the commitment was made

Context

The Morning Star Company is a world-leading vertically integrated food processing company. We began in 1970 when Chris Rufer, our founder, opened shop as a one-man owner/operator trucking company, hauling tomatoes from fields to tomato factories in California. We’ve grown rapidly and, today, are the world’s largest processor of tomatoes, with vertically integrated operations ranging from fields (greenhouses, transplanting operations and farming operations), to harvesting and transportaion, and finally processing. We have facilities located through California’s fertile San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys.

Early in his career, Chris developed some unique ideas about management and organizations, and when he expanded into the processing business (building the first Morning Star factory) he met with all of Morning Star’s colleagues (only a handful at the time) and they decided Morning Star would operate differently. At their first meeting, at a small farmhouse on a dirt road on the outskirts of Los Banos, CA (the temporary headquarters while the first factory was under construction) he asked the question: “what kind of company do we want this to be?”. Their answers led to a fundamental philosophy about organizations–a philosophy that said:

So, in that small farm in Central California, Morning Star was re-born as a fully self-managed enterprise. The company has never instituted any sort of formal hierarchy or managerial structure.

Some History

Chris realized very early on that this new way of organizing, while it was attractive to all involved, and made intuitive sense to everyone within the company, would be easier to achieve when we were small. So, soon after those first colleagues laid out the idea of a fully self-managed enterprise, Chris came up with the idea of a document–a contract of sorts–between colleagues. It wouldn’t be a job description, or an employment contract. Rather, it would be a tool that each colleague would use to outline his commitments to his fellow colleagues. Central to this idea of self-management was the realization that in an organization of any size, almost nothing happens in a vacuum; there are countless interdependencies amongst colleagues, and the strength of the organization depends on the degree to which each colleague clearly defines his commitments to his colleagues–and the degree to which he lives up to those commitments.

So Chris proposed a framework for a document which he called the Colleague Letter of Understanding (or CLOU). This CLOU would be the primary tool that Morning Star colleagues would use to coordinate and organize themselves. Each colleague within the enterprise would have a CLOU–which they, personally, would be responsible for crafting in collaboration with their key colleagues (or, in Morning Star lingo, their “CLOU Colleagues”). This CLOU, when complete, would represent that colleague’s commitment to his CLOU Colleagues. Each CLOU would include:

In the early days, the CLOU was exactly what is implied by the name: a letter–a paper document that each colleague filled out, at least annually, and then reviewed with his CLOU Colleagues to ensure agreement. As the company grew, though, and expanded into new areas with additional locations and an exponentially greater number of colleagues, it became evident that, while the fundamental premise was sound, and was built on a philosophy that all involved were even more committed to (it had, after all, helped to build a very successful company–and colleagues loved it), the CLOU document in its current form wasn’t going to work in the long-term. A paper document filled out annually was a great start, but was easily forgotten–especially when you had a dozen colleagues you worked closely with. And so, when responsibility for a particular item was unclear, there was a need to go back to the “file” and pull out the current CLOU. Which prompted another pain point: Morning Star was growing–rapidly. Change was a constant, and an annual review of CLOUs was good, but wasn’t nearly often enough to reflect the rapidly changing nature of the enterprise. So more often than not, change or uncertainty would breed hesitancy, and eventually someone would step in and just take on the issue at hand rather than circling back to the responsible colleague to try to address the performance gap (remember, we’re self-managed, which means we are responsible for addressing failures of our colleagues to live up to their commitments; no “anointed” manager to run to).

The Project

This was the state of things when, In 2006, I rejoined Morning Star. My recent business experience had birthed in me a passion for effective organizations, and when I came aboard, I wanted to work on advancing Self-Management. Chris laid out a vision for a more dynamic “digital” CLOU, and I began working on an outline. A few short months later, a new colleague, Ron Caoua who had extensive systems experience, came aboard to build the software.

Ron built the prototype, we demoed it, and then he worked with an outside developer to build the final version. We rolled it out in 2007 with much fanfare. We brought computers into the conference rooms at each of our locations, and brought groups of 15 or so colleagues in, one after another, to train them. It was a bit of a shock for some; some of our colleagues have had minimal experience working with computers. Over the course of a few weeks, though, we trained nearly everyone, and had helped nearly every colleague build their first CLOU.

The impact of the software was subtle, but important. First, it’s dynamic; it has the ability to reflect the real changes in content or context of individual’s responsibilities within the enterprise. In fact, a CLOU can now be changed daily, if necessary. Further, it allows colleagues to immediately view their colleagues’ CLOUs–giving a much more ready view into who is responsible for what–even if a colleague isn’t directly related to you. It, essentially, makes the world that is Morning Star a lot smaller.

For example, a colleague recently was telling me about an email he received that, initially, made him a little angry. It referred to problem the sender was having, and the sender was seeking his help in rectifying the particular problem. His initial response was to write a terse email in response that basically said, “this is YOUR job; figure it out and stop trying to pass the buck.” But before he hit send, he decided to take a look at the senders CLOU; he was surprised to learn that the issue the sender had sent him wasn’t any part of that colleague’s Personal Mission. In fact, the sender had taken initiative to try to recruit my colleague, who they felt had the requisite expertise, to take care of the issue–a pretty important customer issue. My colleague spent some time looking through the CLOU system, and was able to identify someone whose mission the issue was somewhat related to; he approached them, outlined the issue and the needed change. That colleague ended up modifying his CLOU to incorporate the necessary process change.

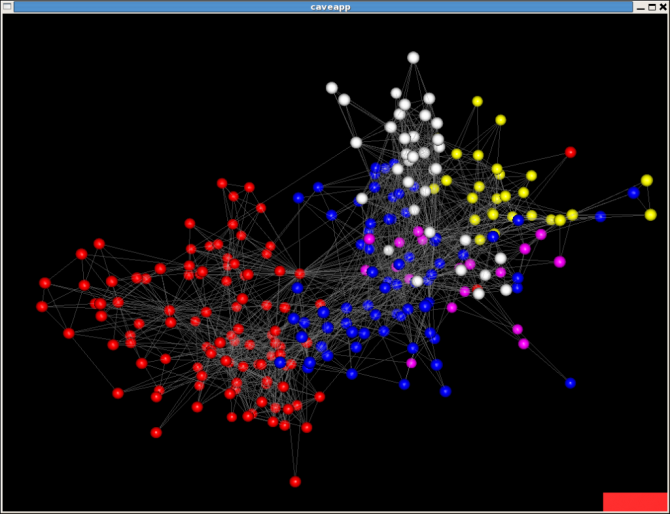

This CLOU relationship model also provides a slightly different perspective as to how our organization is structured. In fact, I would say that the network of relationships forged through the various CLOU connections serves as our “org chart”. It’s not a traditional org chart, by any means: it’s not based on any appointed hierarchy (remember, there are no titles and no formal hierarchy within Morning Star). But it’s an org chart that’s based on the real relationships within the enterprise–a network. It’s also dynamic–in that it can change based on changing circumstances (and does), and contextual–in that the important relationships depend on the nature of the current situation. Below is a print of the network generated by a subset of our colleagues and their CLOU relationships. Identifying information has been removed, but it’s color coded based upon physical location

Moving Forward

The CLOU system has been in place and utilized by most colleagues within the enterprise for nearly four years. While the application provides an effective platform for documenting colleague commitments and relationships, and is completely open and transparent, it is still somewhat static.

Our vision has always been to have a system that is foundational to how our colleagues coordinate, and we’ve made huge strides toward that vision by turning the CLOU into a more dynamic, social network based software. But implementing the software also served to expose new opportunities that we are currently working to take advantage of.

First, we realized that the network element of the CLOU could be enhanced if we could incorporate a colleague rating system into the software. In 2010, Ron and I, working with an outside software developer, rolled out a colleague review system that allows colleagues to review their CLOU Colleague’s performance. The review (which is open–not anonymous) asks each person to provide very detailed feedback directly to each of their CLOU colleagues regarding that colleague’s individual performance and success in achieving their commitments to the rating colleague.

We also, just this year, rolled out a web-based system called “Steppingstone”. This software will serve as the backbone for our enterprise metric reporting. Our philosophy has always been that continuous improvement requires detailed performance reporting to each individual within the enterprise of data relating to each activity that they have accepted responsibility for. Steppingstone data historically, though, has always been fed back to colleagues through a melange of reports and systems, and hasn’t historically been integrated into the CLOU software in any way–other than that colleagues list those steppingstones for which they commit to take responsibility from within the software.

We realized that what we have in place now is only the tip of the iceberg. Our revised vision for CLOU–which we are currently working on–completes the “loop”. In our next version of the software, colleagues will be able to draw from a “menu” the specific activities that they are committing to. The software will still have the flexibility to allow any colleague within the enterprise to expand on the menu (that is, it won’t be “locked down”), but edits will be to the “master” map of the enterprise, and colleagues will then associate themselves with segments of that map. This will enable a more graphically intuitive view of the enterprise, and the colleagues responsible for each area.

Equally important, though, is that when a colleague takes responsibility for activities by selecting them into his CLOU (in the forthcoming version) the corresponding Steppingstone measures will come along with those activities–as well as the relevant reports. This incorporates live (or close to real-time) reporting directly into the colleague’s CLOU. Our vision is that the “home page” of the CLOU will turn into a sort of scrolling “feed” of information. Your home page will update to show updates to key Steppingstones, as well as a running feed of Steppingstone information for your CLOU Colleagues.

Challenges and Solutions

The obvious challenge is the one that drove us to create this software in the first place:

Challenge: How do you create a platform to enable effective self-organization amongst colleagues?

Solution: CLOU, as a concept, is really central to how we organize at Morning Star. Conceptually, the idea of the CLOU isn’t intuitive for many when they come aboard (and, in fact, we have integrated a CLOU planning segment into our Self-Management Orientation that all colleagues participate–and we have a handful of colleagues who are designated facilitators to assist colleagues, especially early on).

But once colleagues understand the CLOU, and really embrace, it becomes central to the way they work–in fact, while you don’t necessarily hear colleagues discussing their CLOUs on a daily basis, they are really a central theme in colleague planning and coordinating conversations and discussions.

But, as indicated above, the static version wasn’t quite as robust as we desired. CLOU version 1.0 has served us well, but we realized that it’s more than just having an accessible platform to store and maintain CLOUs; the system needs to be dynamic–and actively feed colleagues performance information as it’s happening–both their personal information, as well as that of their CLOU Colleagues. That’s really the core of the improvements we are building now in CLOU 2.0.

I don’t think that we could ever have envisioned this dynamic “feed” of information, though, without building this first version of the software–in large part because this network of relationships is fundamental to the “feed” concept.

Challenge: Creating an organizational structure that’s built by colleagues within the enterprise, but ensures we have “all the bases covered”.

Solution: This is one that we didn’t really envision when we set out to build the software. The initial version of the software was structured so that all entries–all activities and all Steppingstones (performance measures)–were free-form; they were, essentially, created by the colleague creating his CLOU.

That’s an OK way of handling it, and it actually has worked just fine, historically, but awhile back we begin to brainstorm, and ask ourselves, “can this tool be used to provide a clear picture of both ‘who-has-what on their plate’ as well as ‘are all the bases covered’?”. Our new version (the 2.0 version that hasn’t been released yet) is built on a process platform. We’ve created an architecture that describes the enterprise in terms of process–and sub-process, and sub-sub-process, etc… And we’ve associated each of our vast number of Steppingstones (performance measures) with those processes and sub-processes. We’re building a graphical interface that colleagues can interact with, both to accept responsibility for some process or sub-process (and the related Steppingstones) OR review who has accepted responsibility for them.

The underlying process architecture is still managed and maintained by everyone in the enterprise (in fact, it is handled something like a wiki–open to all colleagues to modify/add-to/subtract from as appropriate), and, in fact, the whole initial process architecture was populated by the colleagues across the enterprise. This was important to us because the process map of the enterprise should really be representative of all of the collected wisdom within the enterprise.

Benefits & Metrics

Organizing is easier. Clear roles and responsibilities–and the ability to quickly, and openly, modify those roles and responsibilities, has greased the skids of the planning and coordinating process, and has made peer-regulation a little less challenging for colleagues.

“Real” Hierarchies are more visible. We don’t have formal hierarchy; rather, we believe authority should flow to you, willingly, by your colleagues, based on your expertise and achievements. This platform allows individuals to freely associate with colleagues based on their perceived abilities. The CLOU software, combined with our peer rating system and end of year compensation process, has begun to make visible the “natural” hierarchies that exist within the enterprise–and further, allows a clear view into the context of those hierarchies.

Lessons

A commitment between peers is much stronger than a job description. This was an assumption we had going into the project, and is really central to our organizational philosophy, but creating a system that facilitated this as we grew was a challenge. Part of the reason for this, I think is that…

Peer-control makes for a more cohesive group of colleagues. Our philosophy is sometimes mistaken for a “lack of management”. That’s not the case at all. We like to look at is as management rich. We ask everyone to become effective managers of their own mission, activities and CLOU relationships. That means they have to plan, coordinate–and sometimes even, deal with difficult performance issues–directly. But building a system that facilitates that planning and coordination to some degree has provided colleagues with a basis for peer-control, and has, in a sense, made this peer-regulation a bit easier.

The Strength of Self-Management is in the relationships between colleagues. We initially set out to create a basic software to allow CLOUs to be readily available, and more dynamic–and we achieved that. But the experience really brought into very clear focus the idea that the strength of the structure really depended on the strength of the commercial relationships between colleagues. Ironically, this idea that individual commitments between colleagues makes for a stronger organization has always been central to our philosophy, but our experience here really intensified this idea–and caused us to realize that the potential for this type of platform was enormous.

Our current enhancements are really meant to further strengthen those relationships. Imagine it as a social networking application of sorts, where your CLOU Colleague’s individual performance information is piped to you as it is happening, and where you provide direct, subjective feedback to colleagues within your network. The technology here is key–and is really helping us to grow without sacrificing our principles of organizing.

I read a recent Wall Street Journal article that made me cringe. The title of the article says it all: “The Unsung Beauty of Bureaucracy“.

The headline, as you might imagine, caught my attention; I couldn’t resist reading it. Quite honestly, I fully expected that the title was of the snarky, sarcastic sort–and that the article would be some sort of scathing expose of the absurdity of bureaucracy.

Imagine my surprise (and the sharp uptick in my blood pressure) when I realized that the authors were serious! The article, in a nutshell, said that we need bureaucracy. That too much freedom is a bad thing. That bureaucracy keeps us safe. Sure, it is a bit restrictive and stifling, and it hampers innovation–but it also keeps bad stuff from happening. The article said that, if there had just been more bureaucracy, the BP oii spill of 2005 wouldn’t have happened. It said that, if there had been more centralized, bureaucratic control, the Airbus A380 fiasco would never have happened.

The authors went on to make a statement so patently absurd that I have to quote it in all it’s glory here:

“By the same token, many government functions may be laden with bureaucracy, but the private sector might not do any better with the same tasks. Like the makers of baby products, governments deal with uniquely sensitive problems, from ensuring that terrorists never get past airport security to keeping deadly germs out of the food supply.”

As I write this, I’m having to break and walk away from the computer every few minutes just to keep from yelling at my computer screen.

Here are my issues with this:

I could rant on for pages here (can my colleagues say “amen”?), but let me summarize for you: it’s a logical fallacy to say that some of the worst examples of business failure in the last decade would have been averted if there were just more bureaucracy–at least if you’re going to use the arguments that these authors used.

But the larger point for me is this: bureaucracy is nothing more than a human technology–a tool that someone invented as a hedge against ignorance and dishonesty. And I won’t argue that bureacracy is not somewhat effective at minimizing the risk associated with ignorant or dishonest people. But it’s effective in the sense that an atomic bomb is an effective way to eradicate a bed-bug problem. It’ll work–but the collateral costs are atrocious. Our job as thinking, innovative human beings is to imagine, and devise, a BETTER technology for limiting the impact of ignorance and dishonesty–a technology that doesn’t have side effects that are as painful as the disease it purports to heal.

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on March 16, 2013.

We heard from a number of incredible thinkers at our recent 2012 Self-Management Symposium (the best so far, by the way). One of our speakers, John Allison, the former CEO of BB&T (check out the video here—you need to register to view it, but registration’s free and there are a lot of cool benefits) gave a deeply profound talk that really forced me to think deeply about our shared values here at Morning Star and the Self-Management Institute.

He spoke on BB&T’s 10 core values, and how those core values have enabled continued success at BB&T.

One that struck me as a “non-mainstream” value (like integrity—everybody SAYS that integrity is a value) was Self-Esteem. Allison made the point that Self-Esteem is a good thing—that you (as an individual) must believe that you are capable of being good, and that you have the moral right to be happy.

But then he went on to discuss the source of self-esteem. Self-esteem can’t be “granted” or “bestowed” by someone else; “you look good in that dress” isn’t really a source of true self-esteem. In fact, many of the things that we look to as a source of self-esteem (like conspicuous consumption or cosmetic surgery) amount to no more than a very, very poor substitute for true self-esteem. Real self-esteem comes from doing productive work. It comes from creating value for others. It’s the accumulation of personal Pride (another of BB&T’s core values), which we derive by doing work that has a purpose, using reason, and exercising independent thinking (another value), in integrity with our principles (yet another value).

Think about that for a second: in order to have self-esteem, you have to have a sense of personal pride in what you do. In order to have pride in what you do, you have to feel that the work you do is productive—that it has a purpose, that you are doing good. Further, in order to have personal pride, and by extension, self-esteem, you have to be working in an environment that allows you to think independently, to exercise reason and to use your individual mind to make optimal and rational decisions.

So maybe you don’t think self-esteem matters all that much; I’d disagree. Answer this question: do you think, in general, people prefer to feel good or bad about themselves? Of course, I think we all agree that people prefer the former. What’s the cost to our organizations, though, when people don’t feel good about themselves? Think about the last time you felt like you were doing completely valueless work—work that was completely irrelevant or unproductive. Was it an invigorating experience? Did it inspire you to lofty, new heights of innovation, productivity and performance? Of course not; that feeling is incredibly demotivating. And, in fact, I suspect millions of people, in countless organizations, are desperate to leave their current job—a job that they hate; why? I believe it’s because their current role is lacking at least one of the key ingredients necessary for individuals to build self-esteem.

Which brings us to what is, I believe, the irony here: if this idea—that self-esteem is the result of doing productive work that has a purpose, and that allows you to exercise reason and independent thinking—has any merit, it means that we humans come pre-loaded with an internal motivational system. We are all internally motivated to do things that will give us a sense of personal pride, and build our self-esteem. And if we do, in fact, have that internal drive for self-esteem, it means that good, productive work is a part of our nature

So why, then, do so many organizations spend so much time talking about “motivating their employees”? I’ve thought a lot about this, because the idea that employees need motivating seems to be at odds with the idea that employees have a internal drive for self-esteem that can only be fulfilled by doing productive work well. The only conclusion I can come to is that far too many organizations have put in place systems that actually REMOVE those ingredients that are so vital to people cultivating healthy self-esteem. They’ve eliminated a sense of purpose from jobs in the enterprise; people don’t have a sense that what they are doing has any large purpose whatsoever. Or people in the organization see their jobs as unproductive—as not doing good things for people (think: mind-numbing, civil servant/bureaucrat). Or perhaps it’s that people in the organization aren’t allowed to exercise reason—to think always, and to question authority. Or perhaps it’s that people aren’t allowed to think independently—they aren’t allowed to exercise their individual judgment to make rational and optimal decisions that they are more than capable of making.

I don’t think I’m too far off the mark when I surmise that many jobs in many modern corporations don’t have most of those ingredients. So it’s no surprise, then, that people in those organizations aren’t motivated—self-esteem (that internal motivator) isn’t a real possibility given the absence of those key ingredients, so people simply disengage and “put in their time”. And so management in those organizations turn to experts seeking answers to, “how do we motivate our employees and achieve higher engagement levels?” when their organizational systems were the culprit that killed the naturally present motivation in the first place!

Irony.

So, here’s my question to you:

Does your organization systematically ensure that people who are a part of that organization can find personal pride in their work, and accumulate healthy self-esteem, through:

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on August 21, 2012.

A 1991 Chrysler LeBaron convertible coupe in good condition, sold on the street, is valued at about $1,100 by Kelley Blue Book. In stark contrast, a 1991 Mercedes-Benz 500SL convertible coupe in good condition, with similar mileage, is valued at about $5,000.

I drove a Chrysler LeBaron for a bit (I borrowed it from my great-grandmother). While I’ve never driven a Mercedes 500SL, based on my generally underwhelming experience driving my grandmother’s car (and possibly as some sort of subconscious response to the covert laughs my high-school friends had at my expense every time I drove Grandma’s car into the high school parking lot), I’d go for the Mercedes any day if I had to choose.

The catch, of course, is the relatively steep price. The Mercedes, even today (some 20 years after the two cars were manufactured) will cost you five times the value of the LeBaron. Some creative entrepreneur, though, came up with a way for car owners to “have the Mercedes experience at the LeBaron price”. They created a body kit (replete with those distinctive blocky Mercedes taillights and star emblem) that can turn a ’91 LeBaron into a Mercedes 500SL.

Well, mostly. Actually, it really only makes your LeBaron look kinda like a Mercedes. I saw one recently, and my first thought was, “there’s something strange about that Mercedes.” My next thought: “that’s something masquerading as a Mercedes.” It struck me that dressing up a LeBaron as a Mercedes isn’t all that different from a lot of management literature that I read. Consultants, writers, thinkers and academics alike spend a lot of energy trying to devise ways to improve management and organizations—an admirable quest (and a goal I share). But so much of what I read is tantamount to wrapping Mercedes-shaped body panels around a LeBaron and calling it a “high-performance, luxury vehicle”.

A “Merbaron Benz”

Much of what I read wraps creative ideas around the same old management philosophies that have served as the foundation of our organizations for over a century. All you really end up with, though, is marginally improved business as usual; incremental improvements that don’t really tackle the fundamentals underlying the way we see management and organizations.

The real thing–a 1991 Mercedes-Benz 500SL

Unfortunately, I think that we who are leaders in organizations have been far more receptive to this model of improving management than luxury car buyers were of the “Merbaron-Benz”. Many companies now refer to their employees as “team members”, and their managers as “team leaders”—a positive step, to be sure. But they stop far short of addressing the fundamental philosophy; very few companies have gone so far as to say, “authority should flow from the bottom up; let’s let the true leader emerge by choice of the ‘team members’.” Many organizations have acknowledged that “worker empowerment” will positively impact their organizations, and so they “empower” their employees to provide input to their managers—who ultimately make the final decision. Again, a great thing; but almost nobody has flipped the underlying philosophy on its head and said, “let’s truly empower employees; let’s build a mechanism by which employees can ‘veto’ their managers.”

The potential for improvement is enormous, but we’re conditioned to management systems that are built on a foundational philosophy that Frederick Winslow Taylor characterized vividly before Congress in 1912 when he referred to:

“the man who is…physically able to handle pig-iron and is sufficiently phlegmatic and stupid to choose this for his occupation is rarely able to comprehend the science of handling pig-iron.”

It’s a sentiment that few of us share, yet our control systems; our arduous processes of getting projects and ideas funded; our rigid methods of defining jobs; our policies of “need-to-know”—they all flow directly from a philosophy that makes the same assumptions about our employees as Taylor made.

So here’s the challenge: let’s approach the reinvention of management beginning with our philosophy. Ask yourself: what are my fundamental beliefs about my employees? Are they uncaring automatons, simply out to take advantage of me? Or are they, at heart, passionate, driven, thinking human beings, with a great deal of insight and expertise? If your answer is the latter, then begin with that as your foundation, and ask yourself: what principles will allow that passion, drive and intellect to flourish? What management systems will focus that insight and expertise toward maximizing the value our organization creates?

When we approach the problem as a matter of philosophy, then we’ll begin to truly re-invent management. Until then, we’re simply driving the same old car with high-performance body panels bolted on.

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on October 8, 2011.

My wife and I went to Costco the other day to buy diapers for our 8-month-old daughter. I’m constantly astounded at the variety of baby products available; it’s a little overwhelming. And diapers are no exception.

There are “Little Snugglers”, “Little Movers” and “Snug & Dry” (I always wonder—if I don’t buy the “Snug & Dry” is there no guarantee that she will remain snug and/or dry?). There’s the leak lock system, or the snug fit system. There are overnites, little swimmers, pull-ups, jean diapers (replete with a denim print) and even a new “green” option—made with hypoallergenic, organic cotton and with a liner made of renewable materials!

And that’s just a single brand!

My wife is far more decisive than I, and she quickly made her decision (we didn’t choose the “green” option), and moved to deciding which size was appropriate for our daughter.

“The size 2,” my wife said, “is for 12-18 pounds; that’s what she has now, though, and they seem a little tight.”

“So let’s go with the size 3, then,” I said. “They’re good from 16-28 pounds. She’s 17 pounds now, and if we buy the 2’s, we might not get through the whole box before she outgrows them.”

“But there are a lot more diapers in the size 2 box,” she says, “than the size 3 box—and for the same amount of money.” That’s the difficult thing about Costco: the size 2 box had approximately 3,100 diapers in it whereas the size 3 box only had approximately 2,700 (I might be a little off on those numbers, but you get my point).

We ultimately settled on the box of size 3 diapers, but as we debated, I scanned the area to see what the size range is for diapers. It appears that you can buy diapers up to a size 6 (which is suitable for children “over 35 lbs” according to the box).

Something occurred to me and later that night I asked my eight year-old son if it would bother him if I made him wear diapers. He gave me a very strange look. “I’m not going to force you to wear them,” I told him, “I’m just curious. What would you think?”

“That would be weird, Dad,” he said, “and embarrassing at school. I don’t need diapers!” He was a little embarrassed, so I let the topic go, but it seemed that there was an analogy there. You don’t have to be a parent to recognize that there’s a general expectation that, at some point, diapers aren’t going to be a necessity any longer. Forget the diapers, though; from a general developmental standpoint, we (as parents) recognize that our job is to ensure that our children develop the skills, talents, knowledge and expertise required to ensure that next year they aren’t facing the same limitations that they are this year.

What I mean by that is, as a parent, your life is one long chain of constantly changing developmental goals for your children. First, your goal is to get them to smile or coo when you speak unintelligible baby talk to them. And when they finally do, you begin to teach them to say “DaDa” or “MaMa”. And then it’s to wave bye-bye or blow kisses, and to crawl, then to walk. Then it’s to count to ten, recognize their colors, or to recognize and say “nose” when you point to your nose.

Soon you’ve moved on to reading and writing, tying their shoes and riding a two-wheeled bicycle. Then it’s on to addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, playing the piano (or violin or the flute—or even golf).

And one measure of our success as parents is the degree to which we aren’t still working on those early things—the degree to which our children have mastered something, and moved on to the next logical area of mastery. We recognize, more than anything, the job of a parent is not a static job; it changes based upon the development of our children, and perception of our success is a direct reflection of the degree to which our children no longer need us to help them in those early areas of development.

Contrast that with the general role of a manager in a traditional organization. I don’t bring this up to disparage managers, and I certainly am not making any generalizations about managers. But there is something to be said here for the underlying system.

Think about this: great managers aside, the system in which managers work doesn’t say much for the manager’s subordinates. The system puts in place pretty rigid methods of oversight—methods that don’t, systematically, allow much room for the development of those being overseen. As an example, it’s generally recognized that one role of a manager is to approve purchases. There’s a rational reason for this; leaders in companies want to make sure their resources are being used appropriately (that is, that money isn’t being wasted) and, perhaps more importantly, that the purchase fits into the strategy or mission of the enterprise. And, on my first day working in a factory (or hardware store or appliance store), that system makes a lot of sense. It’s unlikely I have enough perspective or expertise to be very effective at making wise purchases that support my organization’s mission past basic office supplies. And that’s probably true of me on day three, and on day 10, and perhaps even on day 30. But sooner or later, that’s not going to be the case any longer. I’m going to learn the organization and our business; I’m going to implicitly understand our mission, and what’s required to achieve our mission. Further, I’m going to develop ideas and concepts that I believe would support us more effectively achieving that mission.

In fact, for all intents and purposes, my level of knowledge, insight and expertise is going to rival that of my manager. But the system doesn’t account for that, does it? Sure, my manager (if she’s a good manager) might recognize this, and might allow me more latitude (thereby bending—or breaching—the policies, but to a positive end). But she might not. The point is that the system itself isn’t designed to assume that employees develop and grow—and that the managerial systems (like purchasing oversight) necessary on day one aren’t likely to be necessary as employees develop.

And what invariably ends up happening is employees end up frustrated, disenchanted and disengaged—just like my 8-year-old son would have been had I forced him to start wearing diapers. And, even if you aren’t interested in engagement or disenchantment, think about this: if the system itself is structured so that my manager is required to approve purchases, even when it’s apparent that I have at least as much expertise as she does, and am equally as committed to the mission as she, aren’t we wasting human effort? And that’s one small example; when we consider the compounded effect of a system that demands this type of relationship all the way up and down the chain of command, the potential costs are staggering.

I know that I’m presenting hypotheticals and concepts that are a little theoretical here, and I can hear you, my Eternal Reader, telling me that you were “a good manager”, and that most of the managers that you encountered were also good managers—and that may, in fact, be true. But my quest here isn’t against “bad managers”; it’s against a system that is inherently flawed. Sure, we can make the flawed system better by hiring good managers, but that doesn’t seem like a very noble quest—and it’s certainly not the stuff revolutions are made of.

This is, as always, first and foremost a call to examine the very philosophies that underlie our organizations. There are inherent flaws in the system as we know it—flaws that can’t be addressed by simply hiring better managers. Kids grow up, and our role as a parent changes. And employees grow; we can’t grow as a company with a managerial system that assumes they don’t.

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on July 20, 2011.

Being a parent is an educational experience, as I’m sure those of you who’ve raised children can attest to. But as a lifelong student of business, and more specifically, management, I wouldn’t have thought that I would learn all the really important leadership lessons from my children.

I did, though. I met this week with a friend who hasn’t had children, and as we discussed leadership, I realized that my view on the subject has really been influenced by my experiences as a parent. Further, I realized that there are a few key lessons that really relate to Self-Management. So I’m going to try to write about them in my next few posts here.

This isn’t, for those of you who are feeling a little cynical, one of those shallow “I learned it in kindergarten” type articles. It’s a small set of leadership principles, the revelation of which I’ve only received as a result of my attempts to be an adequate parent.

So here goes.

Lesson #1: People Will Try to Live Up to Your Expectations

I guess it’s a little cliché, but hear me out before you deem this post shallow; I think you’ll be surprised.

I learned early on as a parent that setting an expectation for excellent things—grades, performance at the karate exhibition or piano recital, a singing part in the church Christmas event—caused my kids to strive to achieve that level of excellence. We talk a lot at our house about being excellent, and about what it takes to be excellent: discipline and hard work, focus, commitment, responsibility and a good attitude. And my children put a great deal of effort into meeting those expectations.

As I pondered their effort, I began to wonder what it would be like if, instead of talking about excellence we talked about mediocrity or “doing enough to scrape by”. Would their efforts and attitudes be different? They would, I think. Here’s why: an expectation is a somewhat overt message that says, in no uncertain terms, “here’s what I think you’re capable of”. That’s a pretty powerful thing to say to a kid: this is what I think you can do; it has an incredible effect on what they actually achieve.

And then there are the parents who constantly berate their children, pointing out their inadequacies, and using every failure on the part of the child as further proof that the child doesn’t have what it takes to be anything of any import. We’ve all seen those parents, and we’ve all met their children; often, the child perfectly achieves the parents’ expectation of him.

I don’t think this is a hard sell, is it? I’m not telling you anything you don’t agree with (at least most of you), to some degree. But if it’s good for a child, is it good for an adult too? Yet our businesses, by design, have this horrible tendency to set expectations depressingly low. There are locks on every thing we can possibly lock—implying we expect someone to steal. An employee has to get a requisition signed, in triplicate by four different managers, in order to purchase gloves and safety supplies—implying we think someone is wasting company resources. Employees have to go through an intricate and, frankly, oppressive systems of checks, and achieve myriad approvals before implementing any sort of meaningful change—implying that we think most of our people are dumb and can’t think through the change process.

I know that there are a few of you reading this—my “but I was a good manager”—friends who are already scrolling to the bottom to tell me why I’m wrong, and that’s OK; I’ll read the comment and likely respond. But before you do, ask yourself if I’m really all that wrong; don’t those things, even if they’re subtle, send some pretty powerful signals to employees about what we expect of them? And, if that’s the “here’s what we expect” message that we send, how likely is it that we’re going to have a strong population of employees in our enterprises who truly perform excellently?

I had a conversation recently with a colleague in one of our affiliate enterprises that really brought this idea into focus for me. This colleague was remarking on the general inadequacy of the colleagues they work with on a regular basis. The people they work with, this colleague said, were lazy, liars who have a tendency to steal. I was a little surprised by this, but listened as the colleague went on to outline the things they had worked to implement in an effort to catch the liars, thieves and sluggards. I wondered if those efforts had resulted in a more honest group of non-thieving colleagues with incredible work ethics? The answer was no. It made me wonder which was the cause and which was the effect.

So here’s my point: Self-Management is built on a foundation that expects quite a lot out of people. There aren’t a lot of locks, because there’s an expectation that people will be brutally honest; there aren’t a lot of hoops to jump through in order to cause change, because people are expected to be the experts who know what change is needed; and people don’t have to get “approvals” to make purchases, because they’re expected to know better than anyone what needs to be purchased in order to perform.

Of course that raises some, “but what happens when…” questions, which we’ll endeavor to answer in subsequent posts!

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on December 24, 2010.

A group of primate researchers some years ago performed a now-famous experiment with a group of rhesus macaques (a pretty common species of monkey used in numerous animal research labs). It’s uncertain what the experiment was initially designed to test, but the results have become oft-referenced in social literature.

The researchers stuck a group of monkeys in a closed room with a tall pole in the center of the room. The pole had a bunch of bananas attached to the top. The monkeys which, of course, enjoy bananas and were easily capable of climbing a pole to reach the tasty snack, immediately began to climb the pole.

This time, though, the researchers didn’t need to get out the fire hose; the other monkeys in the room did the job for them! They gathered around the pole and, collectively, yanked the new monkey back to the ground! The monkeys in the room who’d had the traumatic fire hose experience were now keeping new monkeys, who weren’t subject to the same experience, from climbing the pole.

Who knows why they did it; maybe it was some noble monkey credo that has something to do with “protecting our fellow monkeys from things that might hurt them”, or perhaps it was a more base response–namely, if I can’t have the bananas, neither can you. It doesn’t really matter; the point is, they carried on the “can’t touch the bananas” tradition.

The the researchers got another bright idea: they decided to replace ANOTHER of the original monkeys and they observed similar, but perhaps more interesting, results: the original monkeys and, now, the first replacement monkey (who’d been yanked off the pole repeatedly by his peers) together proceeded to pull the new arrival from the pole every time he tried to climb it.

And this went on; the researchers, one by one, would replace one of the original monkeys with a new, oblivious monkey and, every time, the results were the same: the entire group would band together to keep the newbie from reaching those bananas. All this without a single “reminder” blast of the old fire hose!

And then came the most fascinating experience of all: the researchers realized that only one of the monkeys in the room was from the original group; he was the only one who’d experienced the fire hose. “What will happen,” they wondered, “if we remove that guy? Will the whole thing break down? Will we have to get out the fire hose again?”

You, by now, probably know the answer to that. They replaced that last guy with a new monkey and, now, not a single monkey in the room had ever experienced that annoying fire hose. Yet the result was the same: when the new monkey tried to climb the pole, the group rallied around and pulled him down. And the pole went unclimbed, and the bananas went uneaten!

So what does this have to do with your organization? Well there are two important lessons here, I think. First, if you’re a leader in your organization (whether by title or by expertise–and MANY of us are leaders in numerous ways), recognize that your actions send a very loud message to those you lead. A few “blasts from the fire hose” from you, and those who follow you will adjust their behavior accordingly but, more importantly, they’ll enforce that behavior with their colleagues. That’s what we call culture: it’s something that’s embedded deep within the organization, and it’s very hard to change.

Which brings me to the second, and perhaps most important, lesson here: your power to influence and perpetuate culture. With the group of monkeys, it quickly became a cultural taboo to try to reach those bananas. And that cultural taboo was reinforced over and over again by every monkey in that room, even past the point where all of the “old-timers” who actually knew WHY the bananas were bad had “passed on”, and all that were left were the newbies, who only knew that THEY’D been yanked down from the pole. And yet they perpetuated that cultural taboo; they reinforced it vehemently.

You are the culture in your organization, no matter who you are. And what you choose to reinforce is what will become the norm. The thing is, often it’s so easy to just go with the status quo, to accept that “it’s just the way we’ve always done it”.

Perhaps, in your case, the “way we’ve always done it” includes a massive hierarchy, with miles and miles of red tape; or perhaps your “untouchable” bunch of bananas is a person who is a tyrant but who is mysteriously accepted. Regardless the actual situation, whether you like it or not, you will be a part of perpetuating that thing in your organization, or changing it; it’s unavoidable.

So, ask yourself these questions: first, in those areas where I’m a leader, am I using the fire hose in the right areas, or am I sending the wrong messages? And, second, as a participant in my organization, am I just becoming “one of the monkeys” and allowing the messed up parts of our culture to simply persist, or am I constantly doing my part to change the things that need to be changed, and reinforce the things that need reinforcement?

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on October 21, 2009.

A few weeks ago, a colleague sent me a well-reasoned note that pointed to what he felt were contradictions between a few of my previous blog posts. He reminded me that Self-Management derives a great deal of strength from the cross-colleague feedback that the organizational model should foster. It forms a sort of self-regulating organization that, theoretically, is far stronger than the traditional hierarchical model in that each and every colleague is charged with addressing and correcting issues they perceive within the organization.

My colleague went on to reference a subsequent post in which I ruminated on the dangers of rudeness in the workplace. In that post I referenced recent research that suggested that rudeness causes overall cooperativeness to diminish and also might actually diminish the cognitive capacity of those who are subjected to rude behavior.

These two premises, my colleague pointed out, seem contradictory. Confrontation, he says, is a vital ingredient in a Self-Managed enterprise (I would argue, actually, that confrontation is a vital ingredient in ANY healthy social organization). But every time, he goes on to say, that he’s confronted someone, the confronted colleague perceives the confrontation as rude.

And he makes a good point: often, he says, the deviant (the one who is engaging in this behavior that so desperately demands correction) has justified the behavior in his own mind and really isn’t interested in hearing what you have to say.

That’s fair and I have no doubt that it happens from time to time.

Finally, my colleague points out that he’s had his life saved by someone who started out the confrontation with something like, “Hey, you $*$#@& idiot!” Essentially, he says, sometimes “rudeness” is the only way to get someone’s attention–and I agree. Particularly when someone’s life is on the line. But most of the time, someone’s life isn’t on the line; the situation is something far more mundane. And those are the situations that I’m interested in.

So I ask you to consider a completely different social environment, one which demands that you confront another from time to time: your marriage (or relationship with significant other). I suspect that most of us (at least those with a reasonably healthy, happy relationship) have found a way to confront our significant other without being rude. In fact, courtesy seems to me to be an earmark of civilized interaction.

What’s the difference, then? Why is it that we think confrontation at work demands brusque, discourteous behavior?

That’s an honest question.

Here’s what I think: confrontation at home is given–and received–with an understanding that this confrontation is intended to better both of our lives. That doesn’t mean it’s enjoyable or even well-received, but there’s an implicit understanding that both of us are committed to this relationship, so this confrontation is simply intended to enhance that relationship.

At work, on the other hand, our relationships with our colleagues are too-often built on wary distrust. We’re generally friendly and get along OK, but we go through our careers driven by this undercurrent of fear–that someone is looking for a way to give me the boot and rob me of my livelihood.

Further, when we’re put in the position where we have to confront another, there’s this feeling of unease about the “aftermath”–that is, what’s this relationship going to be like after the dust settles?

And these two phenomena, together, manifest themselves all too often as unproductive confrontations that do more damage than good.

Does that make sense?

How can we solve it?

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on September 1, 2009.

I’ve read a great deal of literature about self-organizing as the most natural method of organizing.

Writers like Meg Wheatley (Leadership & The New Science), Steven Johnson (Emergence) and Deborah Gordon (Ants at Work) have spent decades studying ants and termites, various herding animals and even groves of trees, and have come to the conclusion that self-organization has long been found in nature. Various insects and other living organisms coordinate, somehow, without any management or leadership whatsoever.

Which poses the question: first, if it’s a natural method of organizing, why is it so rarely seen in organizations? Second, if ants can do it, why is it so difficult for us humans? I mean, ants have a brain the size of…well…an ant brain! They have, comparatively, no intelligence whatsoever. Yet they accomplish SO MUCH without a leader at all. Must be easy, right?

Wrong.

Because people skydive.

The thing is, humans, with all their superior intelligence, also have this thing called “rational thought”. Ask yourself: is it smart to skydive? If you’ve gone skydiving, don’t take that the wrong way; it’s not intended to be critical of skydivers. Rather, it’s intended to point out that, if we are hard-wired as a living species to self-preserve (that is, we’re designed with this internal drive to keep ourselves alive), then why would anyone get in an airplane, fly up a few thousand feet, then jump out—only to land right back at the spot where they started? There’s no real potential benefit associated with jumping out, and a WHOLE LOT of potential downside.

You don’t see ants skydiving, do you? Or termites—or even monkeys. We humans have this incredible ability to override our natural tendency toward self-preservation. We want the “rush” that comes along with skydiving, so we override the natural instinct that says “REALLY DANGEROUS!! DON’T JUMP OUT OF AIRPLANES (unless they’re on fire)”.

And if we’re able to override that instinct for self-preservation because it’s fun, then we must be able to override an instinct for, say, interpersonal conflict—because it’s NOT fun. That’s the hardest part of Self-Management: the responsibility to address inappropriate behavior. And approaching someone that’s doing something inappropriate is most assuredly NOT fun. So we rationalize our way out of it.

And if we can rationalize our way out of interpersonal conflict because it’s not fun, then it stands to reason that we can rationalize our way out of coming to work on time, and working efficiently on a consistent basis, and spending company money judiciously.

Ants can’t do that. They can’t turn off the work ethic; it’s just built in. And they can’t decide to steal or to ignore other slackers. It’s pretty easy to organize when you get rid of rational thought.

But then in the absence of rational thought—which brings with it creativity and innovation, we’d never progress. So I’m not advocating “turning off” the rational part of our minds. But I am making the case that business has traditionally used management as a “police force” to keep employees from mis-applying their ability to think rationally.

The question, though, is this: is there a more effective way? Self-Management makes the case that there is. In fact, one of the fundamental principles of Self-Management is that colleagues in the Self-Managed organization have an obligation to address behavior that detracts from the enterprise mission. In essence, it’s self-regulating.

It means that instead of one pair of eyes charged with safeguarding the enterprise, EVERY eye is charged with safeguarding the enterprise. Seems like it might be an advantageous concept!

– Originally published by The Self-Management Institute on March 20, 2009.